The next part of my London adventure took me from Trafalgar Square - where I nearly lost a leg - to the British Museum.

With Covid-19 in mind, I was resolutely keeping to open spaces, and staying out of shops. The British Museum would of course be an 'inside' space, but surely its halls and stairways and galleries would be large enough to pose no risk.

I began with a quick look at St Martin-in-the-Fields church, which stands slightly north-east of Trafalgar Square, and is one of London's famous landmarks. You might assume that it's a church that Sir Christopher Wren designed in the rebuilding of London after the Great Fire of 1666. But no: it was a later commission, designed by James Gibb, and it went up in the mid 1720s. Here it is.

Very classical, very impressive. Nowadays renowned for its orchestral concerts and other events. I ventured inside, only to find that a late-morning reading was in progress. I could hardly wander about inside, taking photographs, while that was going on, so I quietly left. Another time.

Walking up towards St Martin's Lane, some typical London sights came into view. Iconic big red telephone boxes you could actually use. And there was the London Coliseum, with its revolving ball at the top. And just before I reached it, a pub called The Chandos, with a figure emerging from a corner of the roof.

I thought that workmen usually manhandled beer barrels at ground level, or lowered them into the pub cellar. But what do I know? Let's hope he never drops it onto passers by!

St Martin's Lane turned into Monmouth Street, and halfway along was a gallery full of artworks. David Bowie stared out at me. An image from the 1980s, I'd say.

The card in the bottom right corner of my shot bore a price of £3,790. I can't remember whether this referred to the Bowie artwork, or something else. But I wouldn't be surprised. An art shop in a good West End location would be an expensive place to pick up something for the home. I noticed a lot of hairdressing salons in the vicinity, all looking very upmarket, and presumably all charging eye-watering prices.

Shaftesbury Avenue was drawing near. I caught a glimpse of an Art-Deco stone frieze and took a slight detour up a side street to see more. It was the Odeon cinema.

My leg was bearing up really well, so I pressed on. A modern glass telephone kiosk came into view, and I was impressed by a small poster on it that bore this striking bit of art:

It could have been the work of Picasso; but the lips made me think of Mick Jagger.

Inevitably, there were other things stuck to the kiosk, such as those advertisements for sex with dominatrices. Later on, when I tried to upload this picture to Flickr, it was bounced back at me. Flickr was playing for safety, saying that my shot might cause offence. That immediately made me feel feel dirty and impure, as if I'd gone out of my way to publish lewd material. I felt accused and embarrassed.

These ladies and their advertisements were just part of the London Scene, and nothing very exceptional. In any case, they were incidental elements in my shot. I do of course see that any photo showing provocatively-clad young women, offering fetish amusement or excitement to kinky men, could be construed as an affront to ordinary women. But - speaking up as an ordinary woman - I wasn't affronted at the time, nor since. Flickr had however intervened to make me feel very uncomfortable, waggling its finger at me as if I were disgusting and degraded.

I think Flickr is ignoring the facts of life, and not crediting me with good judgement and a broad-minded viewpoint on matters of casual sleaze. London is not a city of saints. I think it's best to be fully aware of what's out there on the streets, and to make one's own considered decision on how bad it is. I can't get worked up about run-of-the-mill dominatrix and bondage services, and I don't want an online photo-hosting company imposing prudish standards on any reportage pictures I may take.

In any case, I've little doubt that the glamorous girls in those pictures were paid actresses. The real girls, the ones with kids to feed, rent to pay, perhaps a drug habit to satisfy, or a parasitic male 'protector' to placate - and quite possibly trafficked from eastern Europe or beyond - wouldn't be so alluring.

And there go you and I, if ever we fall on hard times. I don't feel insulted by those advertisements, only saddened. Enticements like these, stuck to bus shelters and telephone kiosks, are just an overt part of a vast, eternal industry that caters for unsavoury men who pay for sex, and expect to get their full money's worth. It must be soul-destroying for the girls caught up in it. I'd utterly hate having to pleasure a succession of men for a living - some of them creepy, some of them violent, all of them sensation-seeking fantasists who see women merely as objects, sex toys, or easy targets for physical abuse.

Let's change the subject.

The building styles in this part of London were a mixture of the traditional and the highly-coloured modern. Three newish blocks appeared, making a nice strong plash of colour against the sunny blue sky.

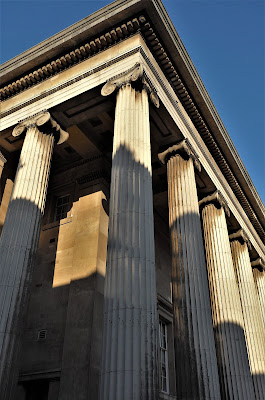

Then, down a side street, I saw the unmistakable classical frontage of the British Museum, all huge columns, which were almost overwhelming when I got closer.

I was so lucky that the sun was out, and shining like that on the front of the Museum!

I had first to pass through a tent where my bag was examined for bombs, knives, sub-machine guns, and canisters of poisonous gas. Really all very friendly. Then I was free to enter.

I hadn't been here for many years. It was exciting to be back. The interior was as cavernous as I remembered.

It would be remarkable if I caught Covid in such a vast space! But of course, I was still wearing a mask.

Now that I was here, what would I see? I couldn't stay over-long. I had to walk back to London Victoria station, and get away from the city before the rush-hour got into its stride and the trains became too full. Inevitably, I confined myself to the Egyptian, Assyrian and Greek sections. Let's start with the first.

Ever since a child I've been fascinated by ancient civilisations, and none more so than Ancient Egypt. Over the years the childhood wonder has been tempered by the realisation that life then was, for most, short and not especially sweet. The Nile Valley and the Nile Delta were hot places plagued with flies and water-born parasites. Some of these were very nasty. I recall being appalled when I learned that one parasitic worm would infest a man's testicles, greatly enlarging them to such an extent that he might end up having to cart them around in a kind of wheelbarrow if he needed to go anywhere. Surely to be afflicted like that was unusual, but probably not very rare. I was puzzled why he didn't simply castrate himself, and get rid of the problem that way. But perhaps there was some legal or religious prohibition against it - or a man's usual reluctance to diminish his 'manhood' or in any way interfere with his 'masculinity', and with it his social standing, no matter what the good reason.

A universal problem was bad teeth. Apparently nothing like a toothbrush has ever been found in any of the tombs, a strange omission when each tomb was kitted out with everything needed for the Afterlife. But dental caries and gum disease weren't the main issue. Enough ancient (and datable) skulls have been found to reveal that everyone's teeth suffered extraordinary wear - slave, merchant, vizier and pharaoh alike. It was the tough, fibrous diet and minute particles of quartz in the bread, the flour being ground by hand and helped along by adding sand. So everyone had the tops of their teeth smoothed away, exposing the softer dentine inside the tooth, and they must have had constant toothache. Quite a few would have developed excruciating pain from abscesses. And of course there were no modern painkillers; just magic spells.

Here are some actual examples that were on display.

So, despite my decades-long fascination with Ancient Egypt, I wouldn't want to be somehow spirited there, even if I could be a royal princess and enjoy a very nice life of luxury. As these tomb murals on display showed:

It looks like a Girls' Night Out, with table service, dancers and a clarinet-and-guitar band. Meanwhile the men were hunting wildfowl down at the river, with one's daughters in tow, watching, and picking flowers by the look of it:

And the staff were herding cattle:

It looks like the Good Life, until you remember that they all had toothache.

But it's the mummies that most people chiefly want to see, and I was no exception. In dim light the rather massive wooden coffins look menacing, but the Museum lighting was bright enough. Although the styling, painting and depiction of the person inside the coffin were conventional and formulaic, it was still possible to get a sense of the dead individual's appearance when alive:

The rather stiff and formal styling did change over time. This late example is (I think) from the Ptolemaic era, approaching the time of Cleopatra and imminent Roman domination:

Doesn't that girl's personality come through? I like the slight tilt given to her head, and her smile.

Elsewhere in the gallery was a woman's coffin - well, she has breasts, hips and a narrow chin - with her body beside it, neatly and rather elegantly wrapped up in the mummification bindings:

If the gilded head on the coffin is a guide, she wasn't much more than forty when she died. Despite being from a rich family - perhaps a royal family - she didn't enjoy a long life. It's rather sad. We take a good long life too much for granted. For so much of human history, it was a rare thing to live into old age, even if in cosseted circumstances. There was no understanding of the true causes of disease and what to do about them. Some people survived, most didn't. Death or disability depended on a god's whim; traditional chants, prayers, sacrifices and spells were all one had. And yet I suppose the Ancient Egyptians would have scorned all our modern treatments, were they offered.

The Museum's Ancient Egypt exhibits were situated mainly on the upper floor, but the particularly large and heavy stone figures and busts were spread out in a long ground floor gallery. There I next went. These were the most impressive of the exhibits, some of them still exuding overwhelming power and majesty. All these pharaohs and deities had a serene and self-confident air about them, as if they knew they would still be around, mostly unblemished, thousands of years after their time. And they were quite right.

For ceremonial (and monumental) purposes, all pharaohs sported a strap-on beard. Presumably the Ancient Egyptians were not a hairy bunch (unlike the heavily-bearded Assyrians) and - to look properly regal - male rulers had to wear wigs on their chin, as well as on the top of their shaved head. This chap has had his fake beard knocked off.

He's looking at those girls. I wonder what's running through his head?

Majestic they may be, but there is little sense of personality. Are these true likenesses? They are all so obviously idealised. And that smooth-faced calmness reveals nothing. Were they cruel and selfish? Or kind and generous? Were they wise? Did they have secret worries? Were they nursing a nagging tooth? Who knows. I suspect that every pharaoh was under the thumb of the priesthood, and that his daily life was dominated by tedious ritual, as well as the humdrum affairs of state. Time off from that would be precious: time with his family; or time spent on exciting military campaigns to quell trouble in Nubia or Palestine, and bring back fresh riches.

The large pantheon of Egyptian gods and goddesses had to be given their proper attention. Every Ancient Egyptian thought much of what these supernatural entities might say if watching, and how their own good or bad behaviour might affect their chances of an Afterlife. Whether they were lion-headed, or hawk-headed, or jackal-headed, the gods and goddesses were demanding and particular, and unforgiving of errors.

Nevertheless, no god or goddess was unjust. And surely this giant figure of (I think) Sekhmet, the lion-headed and supposedly-fierce goddess of war, is no blood-lusting monster. I think she looks strong but also wise. Her special role was to protect the pharaoh in battle, and when he died to escort him to the Afterlife. Otherwise, to send plagues and other testing disasters to Egypt. But I find it hard to believe that she was capricious and mean.

This post is long enough now, so I'll continue my time at the British Museum in the next one.

British Museum.JPG)

British Museum.JPG)

British Museum.JPG)

British Museum.JPG)

British Museum.JPG)