I haven't explained why I curtailed the Northumbrian part of my recent holiday. The story is this.

During the second day at Old Hartley in Northumberland it seemed to me that something was amiss with my fridge-freezer. The fridge wasn't as cool as it should be, nor was the stuff in the freezer as rock-hard frozen as usual. Well, the site was full up and it was summer - that could mean, on an older site anyway, that the shared electrical supply might not be quite as good as usual. Kettles might take longer to boil. And fridges wouldn't be as cold unless you turned the coldness setting up. I did that. But, returning in the early evening, I noticed no great difference.

Next morning (on my third day there) it was clear that I had a meltdown on my hands. A defrost had set in. The fridge-freezer was part of my caravan's original equipment, and therefore going on for twelve years old. It might well have reached the end of its working life. It would spoil my holiday to be without a fridge-freezer. I was geared up to cooking all my meals in the caravan, which required storing a quantity fresh foodstuffs in a cold space. Enough for three or four days. I could of course go shopping every day instead, but that would be an absolute bind. Nor did I have a budget for eating out every single evening.

I was a long way from Sussex, and had more than half my holiday yet to come. It would be massively inconvenient and annoying to be without a means of keeping milk and food cold. I decided to cut the holiday short and go home.

So before going out on the third day - I had long arranged to see a friend for that entire day - I cancelled my forward site bookings, and just set up a single night at Stamford, as an overnight stop on the long journey back to Sussex.

But while out on that third day, an idea occurred to me. Caravan fridge-freezers were very simple beasts, with almost nothing to go wrong. There was no kind of motor or pump in them, because they had to be silent in operation in the confined interior of the caravan, and in any case cope with jolting and other movement while towing. They used electricity or gas to set up a passive cooling cycle that gradually extracted heat and let it drift away outside through grilles on the side of the caravan. This was thermostatically controlled.

Now (I thought from time to time during the day) suppose that thermostat wasn't broken, merely temporarily unable to do its stuff? There was something at the back of the freezer - a kind of dark metallic knob, whose purpose had remained unknown to me all these years - that might be the thermostat. The freezer was closely packed with packets of meat and fish I'd made up at home. What if a wrapping had somehow covered the thermostat, sealing it off, and made it 'think' that the freezer as a whole was very cold, when in fact it mostly wasn't at all? (And where the freezer led, the rest of the fridge followed, so that everything was warming up)

Another point. As I had locked up to go out, I had run my fingers over the exterior grille. I definitely felt some warm air. That surely meant the fridge-freezer wasn't dead. It was still working, albeit below par.

Once home, I emptied the freezer to see whether the situation was as I thought. And I was right.

Somehow a plastic food bag had stuck itself over what I took to be the thermostat, sealing it in. It was sampling only a tiny bit of freezer airspace, and erroneously deciding that it was cold enough. I peeled away this plastic bag. In fact I took out everything, transferring the things I could eat within a day or two into the fridge section, and binning the rest. It wasn't actually a serious financial hit: maybe just £20 worth of this and that lost.

Before I went to bed, I noticed a difference. It was definitely colder in the fridge, and in the freezer things were getting arctic again.

Problem solved, then! I could carry on with my holiday. Except that I'd already cancelled it all. I'd have to get up to the Old Hartley site office first thing next morning, and see if I could have my five cancelled nights back. then reinstate the other bookings.

I was too late. My pitch was now allocated to new arrivals, and I'd have to move on, cutting short my Northumbrian holiday. Back at the caravan, I did what I could to salvage my original plans. A lengthy session on the Club website. I'd have to forego the Peak District and the Cambridge area. I could have a few more days at Stamford instead. I consoled myself with the thought that I was saving money by lopping a week or more off my original holiday. And in any case, the threat of a big expense - a new fridge-freezer once home - was lifted!

I could still have five nights at my next destination, Bridlington, as first intended - but it would come sooner.

I dare say that 'true caravanners' of the Old School will scoff at my running for home, just because I thought my fridge-freezer had packed in. I don't care. I expect luxury on my holidays - well, comfortable living, anyway, with all appliances working properly. I am not going to rough it. My caravan is a mobile hotel room, not an endurance capsule. I am not on holiday to test myself in any way: I want a hassle-free time. So, let 'em scoff.

Tuesday, 31 July 2018

Sunday, 29 July 2018

Bastles and castles

This post is about Woodhouses Bastle and Harbottle Castle, both in the hills of western Northumberland.

This is Border Country, a broad area either side of the Scottish-English border, notorious up to the late seventeenth century for lawlessness and violence. There would be raids on either side to carry off livestock and other things of value - the odd hostage too, no doubt. Some raiding was a matter of sheer acquisition, but it was often a matter of punishment for some slight or disrespect, degenerating into frank retaliatory feuding.

Sparked off again and again, these raids went on and on for centuries until eventually curbed by central government measures to suppress the active participants, who were known as Reivers - see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Border_Reivers. Their depredations were later romanticised in Victorian times, but there was nothing very noble about any of their exploits. This was vicious local robbery and pillage - essentially warfare - and nobody living in Border Country could expect any rare state of peace to last for long. I remember a late-1960s TV series called The Borderers, which painted a vivid picture of life on the Scottish side of the Border. Surprisingly, Wikipedia has a decent article about this old TV series (who does all this research?) - see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Borderers.

Powerful men along the Border would have proper castles at their disposal, or at least a large, fortified tower house like a castle keep, called a peel tower. Here's one I saw at Elsdon, now in private hands. (The large ground floor window would be a late addition)

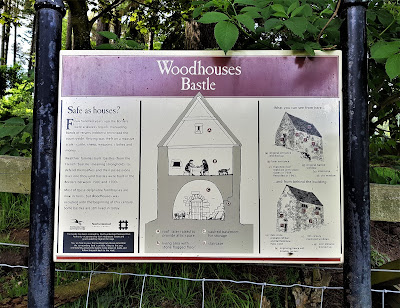

A local man of importance (plus his family and retinue) would be safe from raiders inside one of these! But everyone with property needed a secure refuge. Humbler landowners, such as hill farmers, who couldn't afford even a peel tower, would at least have specially-constructed stone houses with very thick walls and very small windows. These were known as bastles. I went to see one of the best-preserved, off a minor road south of Holystone. It was Woodhouses Bastle.

This is Border Country, a broad area either side of the Scottish-English border, notorious up to the late seventeenth century for lawlessness and violence. There would be raids on either side to carry off livestock and other things of value - the odd hostage too, no doubt. Some raiding was a matter of sheer acquisition, but it was often a matter of punishment for some slight or disrespect, degenerating into frank retaliatory feuding.

Sparked off again and again, these raids went on and on for centuries until eventually curbed by central government measures to suppress the active participants, who were known as Reivers - see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Border_Reivers. Their depredations were later romanticised in Victorian times, but there was nothing very noble about any of their exploits. This was vicious local robbery and pillage - essentially warfare - and nobody living in Border Country could expect any rare state of peace to last for long. I remember a late-1960s TV series called The Borderers, which painted a vivid picture of life on the Scottish side of the Border. Surprisingly, Wikipedia has a decent article about this old TV series (who does all this research?) - see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Borderers.

Powerful men along the Border would have proper castles at their disposal, or at least a large, fortified tower house like a castle keep, called a peel tower. Here's one I saw at Elsdon, now in private hands. (The large ground floor window would be a late addition)

A local man of importance (plus his family and retinue) would be safe from raiders inside one of these! But everyone with property needed a secure refuge. Humbler landowners, such as hill farmers, who couldn't afford even a peel tower, would at least have specially-constructed stone houses with very thick walls and very small windows. These were known as bastles. I went to see one of the best-preserved, off a minor road south of Holystone. It was Woodhouses Bastle.

As you can see, it's a stout little building with a living chamber well above ground level, accessed by ladder only. How babies and small children got up there, it's hard to say - in a basket hauled up by rope, perhaps? Underneath is a separate, heavily-barred space for the best of the farmer's beasts. Having had word that raiders were on their way, the farmer would, if there were time, get his best cattle securely inside, then order his household and helpers upstairs, drawing in the ladder after them. Then they would sit it out.

To some degree the set-up was impregnable. The people inside couldn't easily be got at. The raiders might consider smoking them out with burning wood, but the trees now growing nearby probably didn't exist then, and the farmer would in any case have ensured that any cover useful to an attacker was cleared away from around the bastle. So beyond a small store of ordinary firewood, or peat, the attackers would have nothing much to make a big fire with. But the raiders wouldn't usually have the time for a siege, not wishing to be attacked themselves if they hung around. So far as valuable possessions went, it was hit and run, smash and grab, as fast as possible. The beasts in the undercroft were more vulnerable, especially if the barred door or gate to their chamber could be forced, but if it would all take too much time the raiders would move off to a less protected farmstead.

Once gone, the farmer would cautiously emerge and put to rights the damage the raiders would have inevitably inflicted on unprotected parts of his property. Poor tenants might contemplate their burnt-out hovels and begin repairs, or a rebuild. And then all would be well until the next raid, which could come at any time. A life then of constant vigilance and anxiety.

Nowadays Woodhouses Bastle looks serene and picturesque. I made my way up to it, to have a close look.

It was still in use until about a hundred years ago, and has since been carefully restored. The original high-level entrance, now blocked up, was in the top-left part of the facing wall in my shot just above. Much later, in peaceful times, easier access was made by making a doorway in the middle of the upper end of the bastle:

This doorway later became the main entrance for the occupiers. But originally it didn't exist, and any attacking Reivers would see only that high-up doorway, and the lower barred one for the beasts, plus a few tiny windows. Very frustrating for them, I dare say.

I wondered what everyday life had been like in a house like this. Surely it was dim inside, with only those very few little windows, and as there was no chimney, it must have been rather smoky. Probably no well, either - so fetching water each day would have been a bind. Sleeping in the bastle would have been no problem - it would be like sleeping in a barn - but cooking and other domestic activities would be awkward. Did the farmer and his household occupy flimsier but more convenient premises close by, most of the time, and resort to the bastle only when a raid was imminent?

I peered through the newer doorway. This was the living space.

Well, not too bad on a bright day, although the windows to the left were another peacetime addition and were not there originally, so it would actually have been a bit darker. But you could live in this if you had to. Swept out, cleaned up, painted and furnished, with a piped water supply and electricity, and you could make it comfortable for basic modern living.

This was the space underneath. And there was a staircase - perhaps this was another later addition in peaceful times, because in the classic bastle there were (for security's sake) no staircases connecting the living space with the undercroft. Its addition now meant that the ground-level doorway (originally just for the beasts) became in effect the 'front door' for a two-storey house with storage at ground level and living quarters above. The stairs would certainly be a lot more convenient than a ladder for fetching in water and foodstuffs, and for upper-chamber access generally.

I walked further around the bastle.

There were the two windows added later, in peacetime. Originally this wall would have presented a solid blank face to attackers.

A carved inscription on the massive ground-floor door lintel was dated 1602:

The iron gate was modern. Originally there would have been a strong barred door of wood reinforced with iron, and you might not have been able to see inside. No, probably not at all. The sheltering farmer upstairs wouldn't want any hay or stores in the undercroft below ignited by a firebrand thrust through the handy gaps in a conventional iron-bar gate. But as it was, I could take a look. So this is the undercroft from the other direction:

Yes, those stairs must be a fairly recent addition, Victorian perhaps. They look too unworn to be centuries-old!

Adjacent to the bastle was a stone outhouse, presumably of much later date.

A pigsty? Who knows.

As you can see from one or two of my shots, the inhabitants of this bastle enjoyed grand views of the Northumbrian countryside. But endured grand discomforts too, with a good chance of being killed.

Not far away, further up the Coquet valley and closer to the higher hills, was the village of Harbottle. Overlooking it was a ruined castle. There was a model of it, and information on its excavation, in Elsdon church:

It looked pretty ruined now, but the name intrigued me and I had to go and see it! Well, ruined it was. And for what you could see of the castle itself, barely worth the effort of climbing the hill it was built upon. But the views were amazing.

The sheep grazing in Harbottle Castle were an assertive lot, and very disgruntled by my presence. They glared at me, as it I were trespassing on their land. Well, from their point of view, I suppose I was. I played it cool, and attempted to soothe them with honeyed words, but I could see that they were unforgiving brutes, and was glad to leave them in peace.

Somewhere up in the hills behind me in that last shot was the Drake Stone, one of those ice-age erratic boulders that inspire awe. But it was a fair way up the side of a hill. It was mid-afternoon and I wanted tea and cake. Something for another holiday in Northumberland.

Back at the car park where my beloved Fiona awaited, there was a standing stone. Not an ancient one. It was erected in 1998.

Nice lettering.

It was a poem called The Sad Castle, and it won a national award in 1997. It was written by a young girl called Felicity Lance, who was attending Harbottle School. See http://www.thejournal.co.uk/news/north-east-news/rhyme-time-carved-rock-4555861. I'm no judge of poetry, but it seems a commendable effort for someone who was then only eight.

Thursday, 26 July 2018

Hang 'em high

Not far from Elsdon in north-western Northumberland, and at the windy south-western edge of Harwood Forest, is a place where criminals were hung in times past. The spot is marked by a gibbet. The gibbet you see nowadays isn't of course the original one, but even so it looks authentic and ready for business if need be. It's called Winter's Gibbet.

Presumably he was the most notorious of the persons hung here. A nearby plaque tells you something about it. William Winter was hung here in 1791 for murdering an Elsdon woman.

Wikipedia (at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elsdon,_Northumberland) regurgitates more of the story:

Elsdon has a grim reminder of the past in the gibbet that rears its gaunt outline on the hill known as Steng Cross. Strangely enough this gallows has no connection with the Border raiders, many of whom met their death "high on the gallows tree". The present gibbet stands on the site of one from which the body of William Winter was suspended in chains after he had been hanged at The Westgate in Newcastle. Today this grisly relic is called Winter's Gibbet. Pieces of the gibbet were once reputed to be able to cure toothache, if rubbed on the gums.

In 1791, a very nasty murder of an old woman, Margaret Crozier, took place. The following quote from Tomlinson's Guide to Northumberland shows the enjoyment which the old writers took in recounting horrors in all their bloodthirsty detail. Tomlinson says:

Believing her to be rich, one William Winter, a desperate character, but recently returned from transportation, at the instigation, and with the assistance of two female faws [vendors of crockery and tinwork] named Jane and Eleanor Clark, who in their wanderings had experienced the kindness of Margaret Crozier, broke into the lonely Pele on the night of 29th August 1791, and cruelly murdered the poor old woman, loading the ass they had brought with her goods. The day before they had rested and dined in a sheep fold on Whisker-shield Common, which overlooked the Raw, and it was from a description given of them by a shepherd boy, who had seen them and taken particular notice of the number and character of the nails in Winter's shoes, and also the peculiar gully, or butcher's knife with which he divided the food that brought them to justice.

The shepherd lad must have had very good eyesight to count the number of nails in Winter's shoes!

The gibbet stands at a high point once marked by an old cross, called Steng Cross. The stone base of this is still there:

It's a rather lonely spot, in a bleak landscape, which would have been even bleaker before Harwood Forest came into being. There are wide views. Perhaps these views were the main reason why a stone memorial was set up here in memory of a couple named Jack and Dorothy Anderson:

He died in 2000, she in 2013, so presumably the stone was planted only in the last few years. I have to say it's terribly hard to ignore the proximity of the gibbet, with all its dismal associations. And that makes it seem an odd place to put a memorial stone. But perhaps there was some special private reason for the stone being where it is.

I am aware of more than one 'Gibbet Hill' in England, and more than one 'Hangman's Stone', which usually marks the spot if nothing else does. But I can't recall ever seeing another complete working gibbet like this. Not a good place to be after dark, I'm thinking...

Cool waters at Lady's Well

I first found out about Lady's Well at Holystone in Northumberland from a TV programme on BBC4 a few years back, about Britain's holy places. Ever since, I've been keen to go and see it, and finally managed to do so in June. I love to seek out mysterious places and enjoy their special atmosphere. I wasn't disappointed.

Holystone is a tiny place in the foothills of the Cheviots, west of Rothbury and further up the valley of the River Coquet. The Well is reached by taking a footpath from the village.

Having parked Fiona, I had only to follow the signs. It's a National Trust property, and therefore it would be well cared for, with straightforward access. My only concern might be that a lot of other people would be there too, dispelling the tranquillity I was hoping for. But fortunately the Well is just a bit too far into the hill country to be easily accessible for casual tourists, certainly not to coach parties, and I found myself alone. Good.

I was nevertheless noticed by a barking dog as I set off from where I'd left Fiona. Shhhh! My walking route clearly led past some pretty cottages, but where was the next finger-post saying 'Lady's Well this way'? Aha...

I climbed over a style (the only one, thankfully) and set off up a well-defined track across open countryside with trees in the distance.

It was a lovely sunny afternoon, and a pleasure to be ambling along. The only disturbance was a regular clanking sound from up ahead. At first I thought it must be workmen, or a farmer, using a metallic tool to pummel something into the ground - a stake or fence post, perhaps. But it was too regular and sustained for that. The noise grew louder as I approached. I still couldn't see what was making it though. Then I had a notion what it might be. On older Ordnance Survey maps at the 1:25,000 scale there had been, in some country areas, references to 'H ram' or 'Hydraulic ram'. When young I'd often wondered what a 'hydraulic ram' was. Surely not a mechanical male sheep? More likely a fixed heavy-duty machine for farmers to use, though for what was a puzzle. With my teens left behind, the question became unimportant and I never went out of my way to find the answer. But now, in 2018, it looked as if the idle curiosity of decades would be satisfied at last.

I looked into the little stream, where indeed the clanking noise seemed to be loudest. And there it was, inside a brick housing. A hydraulic ram, in the flesh. Clank...clank...clank...

Its purpose must clearly be to pump water, or perhaps regulate the flow of water.

There you are: 'Blake's Hydram' on the plate. How did it work? I thought of household cisterns, but it presumably functioned on different lines, and it wasn't very obvious what might be making that loud metallic clanking noise. But at least the source of it was explained. (While writing this, I've found a Wikipedia article on hydraulic rams, which gives all the information an ordinary person could possibly want - see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hydraulic_ram)

The noise receded as I walked on. The hoped-for serene atmosphere at the Well wouldn't be spoiled after all.

I reached the trees. There was a low stone wall topped by a wooden fence, with a wooden gate, and an NT sign close by.

Holystone is a tiny place in the foothills of the Cheviots, west of Rothbury and further up the valley of the River Coquet. The Well is reached by taking a footpath from the village.

Having parked Fiona, I had only to follow the signs. It's a National Trust property, and therefore it would be well cared for, with straightforward access. My only concern might be that a lot of other people would be there too, dispelling the tranquillity I was hoping for. But fortunately the Well is just a bit too far into the hill country to be easily accessible for casual tourists, certainly not to coach parties, and I found myself alone. Good.

I was nevertheless noticed by a barking dog as I set off from where I'd left Fiona. Shhhh! My walking route clearly led past some pretty cottages, but where was the next finger-post saying 'Lady's Well this way'? Aha...

I climbed over a style (the only one, thankfully) and set off up a well-defined track across open countryside with trees in the distance.

It was a lovely sunny afternoon, and a pleasure to be ambling along. The only disturbance was a regular clanking sound from up ahead. At first I thought it must be workmen, or a farmer, using a metallic tool to pummel something into the ground - a stake or fence post, perhaps. But it was too regular and sustained for that. The noise grew louder as I approached. I still couldn't see what was making it though. Then I had a notion what it might be. On older Ordnance Survey maps at the 1:25,000 scale there had been, in some country areas, references to 'H ram' or 'Hydraulic ram'. When young I'd often wondered what a 'hydraulic ram' was. Surely not a mechanical male sheep? More likely a fixed heavy-duty machine for farmers to use, though for what was a puzzle. With my teens left behind, the question became unimportant and I never went out of my way to find the answer. But now, in 2018, it looked as if the idle curiosity of decades would be satisfied at last.

I looked into the little stream, where indeed the clanking noise seemed to be loudest. And there it was, inside a brick housing. A hydraulic ram, in the flesh. Clank...clank...clank...

Its purpose must clearly be to pump water, or perhaps regulate the flow of water.

There you are: 'Blake's Hydram' on the plate. How did it work? I thought of household cisterns, but it presumably functioned on different lines, and it wasn't very obvious what might be making that loud metallic clanking noise. But at least the source of it was explained. (While writing this, I've found a Wikipedia article on hydraulic rams, which gives all the information an ordinary person could possibly want - see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hydraulic_ram)

The noise receded as I walked on. The hoped-for serene atmosphere at the Well wouldn't be spoiled after all.

I reached the trees. There was a low stone wall topped by a wooden fence, with a wooden gate, and an NT sign close by.

I stepped through the gate and into an enclosure with a quiet rectangular pool at its centre. It was very peaceful and very shady, a good place to spend time pondering over life in general. I walked slowly towards the pool.

It was an ancient spring, but the Celtic cross erected in the centre was fairly modern. So was this chappie, presumably intended to be the St Ninian referred to on the NT plaque:

I festooned myself about him, in case he was lonely. Ninian and me, yeah.

I dipped my hand into the water. It was deliciously cool. And so clear.

Then I walked around the pool. The scene changed as I moved. It really was a nice spot.

I discovered a posy of small flowers left at the base of a tree. Somebody had come here to think of a loved one.

The atmosphere of the place would soothe away any worries or concerns. I had nothing on my mind, but still didn't want to leave. But I couldn't linger too long. I had more exploring to do in these parts!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)