This is Border Country, a broad area either side of the Scottish-English border, notorious up to the late seventeenth century for lawlessness and violence. There would be raids on either side to carry off livestock and other things of value - the odd hostage too, no doubt. Some raiding was a matter of sheer acquisition, but it was often a matter of punishment for some slight or disrespect, degenerating into frank retaliatory feuding.

Sparked off again and again, these raids went on and on for centuries until eventually curbed by central government measures to suppress the active participants, who were known as Reivers - see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Border_Reivers. Their depredations were later romanticised in Victorian times, but there was nothing very noble about any of their exploits. This was vicious local robbery and pillage - essentially warfare - and nobody living in Border Country could expect any rare state of peace to last for long. I remember a late-1960s TV series called The Borderers, which painted a vivid picture of life on the Scottish side of the Border. Surprisingly, Wikipedia has a decent article about this old TV series (who does all this research?) - see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Borderers.

Powerful men along the Border would have proper castles at their disposal, or at least a large, fortified tower house like a castle keep, called a peel tower. Here's one I saw at Elsdon, now in private hands. (The large ground floor window would be a late addition)

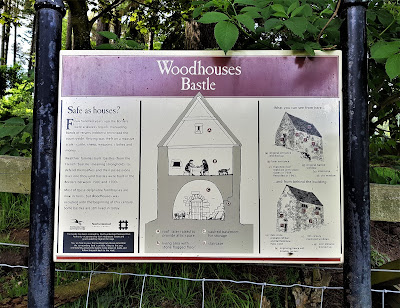

A local man of importance (plus his family and retinue) would be safe from raiders inside one of these! But everyone with property needed a secure refuge. Humbler landowners, such as hill farmers, who couldn't afford even a peel tower, would at least have specially-constructed stone houses with very thick walls and very small windows. These were known as bastles. I went to see one of the best-preserved, off a minor road south of Holystone. It was Woodhouses Bastle.

As you can see, it's a stout little building with a living chamber well above ground level, accessed by ladder only. How babies and small children got up there, it's hard to say - in a basket hauled up by rope, perhaps? Underneath is a separate, heavily-barred space for the best of the farmer's beasts. Having had word that raiders were on their way, the farmer would, if there were time, get his best cattle securely inside, then order his household and helpers upstairs, drawing in the ladder after them. Then they would sit it out.

To some degree the set-up was impregnable. The people inside couldn't easily be got at. The raiders might consider smoking them out with burning wood, but the trees now growing nearby probably didn't exist then, and the farmer would in any case have ensured that any cover useful to an attacker was cleared away from around the bastle. So beyond a small store of ordinary firewood, or peat, the attackers would have nothing much to make a big fire with. But the raiders wouldn't usually have the time for a siege, not wishing to be attacked themselves if they hung around. So far as valuable possessions went, it was hit and run, smash and grab, as fast as possible. The beasts in the undercroft were more vulnerable, especially if the barred door or gate to their chamber could be forced, but if it would all take too much time the raiders would move off to a less protected farmstead.

Once gone, the farmer would cautiously emerge and put to rights the damage the raiders would have inevitably inflicted on unprotected parts of his property. Poor tenants might contemplate their burnt-out hovels and begin repairs, or a rebuild. And then all would be well until the next raid, which could come at any time. A life then of constant vigilance and anxiety.

Nowadays Woodhouses Bastle looks serene and picturesque. I made my way up to it, to have a close look.

It was still in use until about a hundred years ago, and has since been carefully restored. The original high-level entrance, now blocked up, was in the top-left part of the facing wall in my shot just above. Much later, in peaceful times, easier access was made by making a doorway in the middle of the upper end of the bastle:

This doorway later became the main entrance for the occupiers. But originally it didn't exist, and any attacking Reivers would see only that high-up doorway, and the lower barred one for the beasts, plus a few tiny windows. Very frustrating for them, I dare say.

I wondered what everyday life had been like in a house like this. Surely it was dim inside, with only those very few little windows, and as there was no chimney, it must have been rather smoky. Probably no well, either - so fetching water each day would have been a bind. Sleeping in the bastle would have been no problem - it would be like sleeping in a barn - but cooking and other domestic activities would be awkward. Did the farmer and his household occupy flimsier but more convenient premises close by, most of the time, and resort to the bastle only when a raid was imminent?

I peered through the newer doorway. This was the living space.

Well, not too bad on a bright day, although the windows to the left were another peacetime addition and were not there originally, so it would actually have been a bit darker. But you could live in this if you had to. Swept out, cleaned up, painted and furnished, with a piped water supply and electricity, and you could make it comfortable for basic modern living.

This was the space underneath. And there was a staircase - perhaps this was another later addition in peaceful times, because in the classic bastle there were (for security's sake) no staircases connecting the living space with the undercroft. Its addition now meant that the ground-level doorway (originally just for the beasts) became in effect the 'front door' for a two-storey house with storage at ground level and living quarters above. The stairs would certainly be a lot more convenient than a ladder for fetching in water and foodstuffs, and for upper-chamber access generally.

I walked further around the bastle.

There were the two windows added later, in peacetime. Originally this wall would have presented a solid blank face to attackers.

A carved inscription on the massive ground-floor door lintel was dated 1602:

The iron gate was modern. Originally there would have been a strong barred door of wood reinforced with iron, and you might not have been able to see inside. No, probably not at all. The sheltering farmer upstairs wouldn't want any hay or stores in the undercroft below ignited by a firebrand thrust through the handy gaps in a conventional iron-bar gate. But as it was, I could take a look. So this is the undercroft from the other direction:

Yes, those stairs must be a fairly recent addition, Victorian perhaps. They look too unworn to be centuries-old!

Adjacent to the bastle was a stone outhouse, presumably of much later date.

A pigsty? Who knows.

As you can see from one or two of my shots, the inhabitants of this bastle enjoyed grand views of the Northumbrian countryside. But endured grand discomforts too, with a good chance of being killed.

Not far away, further up the Coquet valley and closer to the higher hills, was the village of Harbottle. Overlooking it was a ruined castle. There was a model of it, and information on its excavation, in Elsdon church:

It looked pretty ruined now, but the name intrigued me and I had to go and see it! Well, ruined it was. And for what you could see of the castle itself, barely worth the effort of climbing the hill it was built upon. But the views were amazing.

The sheep grazing in Harbottle Castle were an assertive lot, and very disgruntled by my presence. They glared at me, as it I were trespassing on their land. Well, from their point of view, I suppose I was. I played it cool, and attempted to soothe them with honeyed words, but I could see that they were unforgiving brutes, and was glad to leave them in peace.

Somewhere up in the hills behind me in that last shot was the Drake Stone, one of those ice-age erratic boulders that inspire awe. But it was a fair way up the side of a hill. It was mid-afternoon and I wanted tea and cake. Something for another holiday in Northumberland.

Back at the car park where my beloved Fiona awaited, there was a standing stone. Not an ancient one. It was erected in 1998.

Nice lettering.

It was a poem called The Sad Castle, and it won a national award in 1997. It was written by a young girl called Felicity Lance, who was attending Harbottle School. See http://www.thejournal.co.uk/news/north-east-news/rhyme-time-carved-rock-4555861. I'm no judge of poetry, but it seems a commendable effort for someone who was then only eight.