One of the things I have missed a lot since mid-March is not being able to enter churches. I don't do it for any religious purpose: I have no faith, no wish to pray or take part in any service whatever. I simply want to enjoy the peaceful atmosphere within.

Even town and city churches have this soft and secret atmosphere, as if time is suspended. But I especially like country churches; and, wherever I am in England or Wales, it's my standard practice to base an afternoon's touring on exploring a string of churches that I've found on the Ordnance Survey map. Primarily to photograph whatever special things they can offer: the architecture, the furnishings, the monuments and artworks, the sometimes dazzling displays of flowers or the fruits of the soil at Harvest Festival time; or just the way the light from narrow windows falls on ancient walls and dry old wooden carvings - and if I'm lucky I'll see the patches of colour from stained glass on the uneven stone slabs between the pews.

The carefully-arranged Harvest Festival flowers, fruit and vegetables in the church at Stockland in Devon, seen in September 2015, remain very vivid in my memory:

There's more than just nicely-arranged flowers to see: country churches reflect the social history of both the nation and the particular locality they serve. So to visit a country church is to touch the life of the village, bellringing included. It doesn't matter that nobody is actually there, and in fact I prefer to have the place to myself. If I choose my day and time carefully, there is often a sporting chance that I can admire the interior and take my shots without being interrupted. If moved, I will get out my fountain pen and leave an appreciative comment in the visitor book, something more meaningful and personal than just the usual 'so beautiful' or 'so peaceful'. I imagine that very occasionally the people who look after these ancient buildings run their eyes down the pages of these books, hoping to see something heartfelt. I hope they find what they want in my own entries.

Nowadays it's not unusual to find that country churches have had a small modern kitchen and toilet installed, and a corner for toddlers and their mums to meet up during the day, with a soft floor and toys. In effect, the local pre-school facility. Sometimes there's space for a small library, with comfortable seating, so that retired people can come and browse - as seen here in April 2019 at the church at Southwick in Northamptonshire:

In April 2018 I found a church in Herefordshire, at Yarpole - the one with the curious detached bell-tower - that contains the village shop and post office!

There are thousands of country churches tucked away around England and Wales, and even in familiar local Sussex there are plenty I've never yet seen. It's a quiet and harmless pleasure, to seek them out, and take away some photographic souvenirs. But I've been denied any of that for nearly three months.

However, from 15th June churches will be unlocked again for 'private prayer', and I'm hoping this will mean they are left unlocked all day long, so that fraught souls can slip away to the place they need at times that suit them best. If so, it's surely also an invitation for people like me to look inside. As ever, I will withdraw silently if I find somebody is there before me, coming to terms with loss, seeking relief from pressing worries, or just sharing a moment with the infinite.

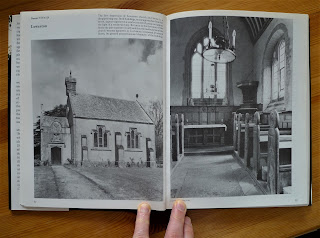

Those last three months have sharpened my appetite, and especially so since discovering that on my shelves at home was a book I'd bought second-hand back in 2018 and not yet read, called Churches the Victorians Forgot. Here it is:

This will give you a taste.

The fingers are of course mine.

I'd actually sought out and visited four of these churches without knowing that Mr Chatfield had included them in his book. I went to one of them, Clodock church in Herefordshire, in April 2018, and these are some of the pictures I brought away - just to show you how a mere tourist will blunder in, shoot the obvious, and miss the deeper things a church can show:

The other three churches I've seen that are in his book are at Warminghurst in Sussex, Parracombe in Devon, and one near nowhere in particular on the Isle of Portland. Well, I might as well give you 'my' tour, so that you can see what kind of shots I took in these places. All are now in the care of the Churches Conservation Trust (see their website at https://www.visitchurches.org.uk/).

First, Warminghurst, seen in February 2018:

Next, Parracombe, seen in September 2018:

And finally St Georges's Reforne, a huge church in an isolated position on the Isle of Portland, seen in September 2017:

Would this last church interior look better in black and white? It would look different, certainly, but I personally think that colour suits it better. However, the exterior views would look more dramatic in monochrome. Hey ho.

So one more week, then - I hope - all church interiors become accessible again. I'm impatient, having made a few new discoveries in the last three months. Such as Lyminster. And Hellingly. And two churches in Lewes. I'll be back.