So far as I can, I live in that world now. Here's a extract from my Money Diary 2020 spreadsheet, showing recorded money transactions over a recent twelve-day period:

If you're curious to see the thing clearly, click on it to get the detail magnified. The rightmost column lists the amounts paid for by credit card, either using my phone and Google Pay, or chip-and-PIN with the actual credit card. As you can see, there were only two cash payments (for very small amounts) in that twelve-day period. I recall that the first one (coffee in The Noah's Ark pub) would have been made using Google Pay, but, being deep in the West Sussex countryside, it wouldn't go through, so I got out a five-pound note. The other, to get a new set of dust caps for my car's tyre valves at Halfords, was paid in cash because I wanted more change for car parking. Another five pound note. In other circumstances, both those payments would have been met with my credit card.

Need I say that my credit card account is cleared in full every month? I don't actually need credit: for me, it's just a convenient way of paying for things I could otherwise buy with money that I really do have in the bank, or in my purse.

I'm not alone. A lot of people nowadays pay electronically, and love it.

There are some who keep on mislaying their phones, and can't say where their credit card is at any given moment. I don't understand why they would be so careless with such essential and valuable items, or what prevents them from mending their ways. But they exist, and they would have a hard time in a cashless world. But it's coming.

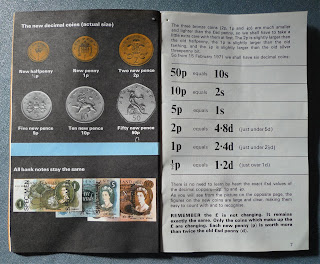

Don't I have any fondness for coins and banknotes? Well, I do. But not the coins and banknotes we have used since 15th February 1971, which was the day Britain said farewell to a money system it had used since Saxon days and adopted decimal coinage. It was out with 'old-fashioned' pounds, shillings and pence, and in with a pound divided into 100 pence, like everyone else in the world. Oh, we had to conform. Harold Wilson's Labour government had, by 1966, decided that Britain needed modernisation in all things, no matter what the changes such a policy entailed.

So in December 1966, this article appeared in the family newspaper, the Daily Express:

At least we still used the pound. A new system based on half a pound - the old ten shillings - had been looked at. Australia and New Zealand had already taken that route. They now used the Australian dollar, and the New Zealand dollar, split into 100 cents. I think it was judged to be 'a bit too American' and so we kept the pound. That didn't please everyone in commerce though:

The grumblings were dismissed.

Instead of cents, we had 'new pence'. It was something; a nod to the past, to the familiar. But for people like me, who grew up on pounds, shillings and pence, the 15th February 1971 ('D Day') was the day our currency died. Or at least lost its soul. I was fond of the old coins. I never felt the same about the new ones, which have now (in 2020) become mere tokens, only the pound coin having any value to speak of.

And none of them carry the august weight of history. Prior to D Day, It was an everyday experience to find that the change in your pocket or purse included coins that were decades old, probably quite worn, but many of them bearing dates that took you well into the past. Before the First World War, and into the late Victorian era perhaps. Spanning the reigns of several monarchs, which was thrilling for children, and a matter for patriotic curiosity if you were an adult. The coins were pretty big, too, and when I was a child in the 1950s much could be bought with them. When your weekly box of groceries could be bought with a ten-bob note, you can imagine just how many sweets a shilling's pocket money might buy!

Once it set the ball rolling on decimalisation, the Labour government (in power from 1964 to 1970) made the process unstoppable. When Ted Heath's Conservative government swept to power in 1970 it was far too late to call a halt. The coins to replace the shilling (with the 5p coin), the florin (with the 10p coin) and the ten-bob note (with the 50p coin) had already gone into circulation. The job was already half-done.

In the run-up to D Day, All households in the country received a booklet giving a pretty thorough briefing on how to mange the changeover. Here it is - click on any of these to enlarge it:

Ministers wore NHS specs then! Designer specs for the masses were thirty years into the future.

It was the era of the corner shop, of being served by a man in a brown overall, and nearly everyone paid in cash.

Apparently it was thought that we'd be clinging to a dual coinage system for some time (as the French had with their Old and New Francs) and would need guidance on how to convert between them. It didn't happen. We got on with it, and adopted New Pence as rapidly as possible, because any other way was an inconvenience.

The government were anxious to assure us that prices wouldn't increase with decimalisation. There would be conversion-roundings both up and down. Of course there were...

Good old Michael Smith and Sarah Brown! Interesting prices. I hoped to do a 1971/2020 comparison but my latest Waitrose receipt shows that I bought none of the things they did. Mine includes items like steak, red peppers, asparagus tips, samphire and sushi. Times and tastes change! Sarah Brown took the bus home and paid 6d (2½ pence) for her fare. Well, that extract from my Money Diary at the beginning of this post shows that I paid £1.60 for a short bus ride of one mile from the centre of Worthing back to the Volvo dealer, where Fiona had just had two new tyres fitted. Probably a shorter journey than Sarah's. So on this evidence, urban bus fares are at least sixty-four times more expensive than they were fifty-odd years ago.

That booklet is a social history document in itself.

I was now going to discuss the old coinage - and the £1 and 10/- banknotes. But I'll do that in the next post.

Did I like any of the new coins? Only one: the tiny ½ new penny coin. I liked it because it wasn't a decimal coin. You don't have fractions in a decimal system. But they had to mint it so that prices wouldn't go up. It had value: it was worth 1.2 old pennies. In 1971 that still made a difference on small items - such as bus fares, or a lunchtime snack.

I don't think it was ever a popular coin. But it had the virtue of adding Something Different And Unusual to our spanking-new decimal system. It didn't fit in. In this it was Very British. I found that little coin most endearing. The old and quirky halfpennies, pennies, threepences, sixpences and half-crowns had all been banished in the White Heat of Labour's plans, but they'd had to provide this odd little coin. It spoiled their Neat Scheme. Hurrah!

The ½ new penny coin lasted only a few years. Its value drained away to nothing during the rampant inflation of the early 1970s, and it was withdrawn. By then it was a nuisance. It was not generally lamented. I doubt if many people remember it at all.

But in its heyday, I had the foresight to pop every one that came my way into a plastic container. I amassed quite a lot of them. I vaguely intended to use them as tokens in card games, or something like that. I never did. They stayed sealed in that container for decades. I had a look at them the other day:

The ½ new penny coin did not have the charm of the old pre-decimal farthing (my favourite bronze coin), but it possessed something of its character. A little coin of small worth, and only in Britain could it ever have existed. And it never would have, if the leaders of commerce had persuaded the government to be even more radical, and introduce a new currency based on the old ten shillings.

A sobering thought: if we had gone for the 'British dollar' or whatever they might have called it, the US dollar would now - in 2020 - be worth nearly twice as much. I can't help thinking that this would have been a Bad Thing.